FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

· WHAT MAKES STREET ART DIFFERENT FROM ‘ART ON THE STREET’?

The term ‘street art’ is increasingly being misunderstood by the public and also in the media, as art on the street. This misinterpretation started back in the early 2010s. At that time, the commercial relevance of artists like BANKSY, Mark Jenkins, BLU, Shepard Fairey and INVADER was increasing. Since the 2000s, they had constantly been gaining in popularity and are today regarded as pioneers of the street art movement.

In this context, it was commissioned artists, art dealers, book authors, tour guides and advertising agencies who, in press releases, on book covers and in interviews, were trying to sell every form of creative expression created with a spray can as the next potential BANKSY and therefore putting a price on street art itself.

But the artistic achievements of these often-anonymous protagonists isn’t defined by a common visual aesthetic or their work in public spaces per se. In this context, the word ‘street’ mirrors, above all, the reflective, critical ways that art activists deal with themes of the street, i.e. of daily life and the challenges faced by society. Whether an artist belongs to this movement in an art-historical sense does not depend on them practicing their artistic work in a public space, however, but purely on the idealistic intentions of their work and how they deal with socially relevant themes.

Street art has always been described by the people who create it as democratic art. But here, democratic refers to the dialogue and discourse opened up by their artistic work across all echelons of society, and not to the fact that everyone can participate in it – in the context of art workshops, for example.

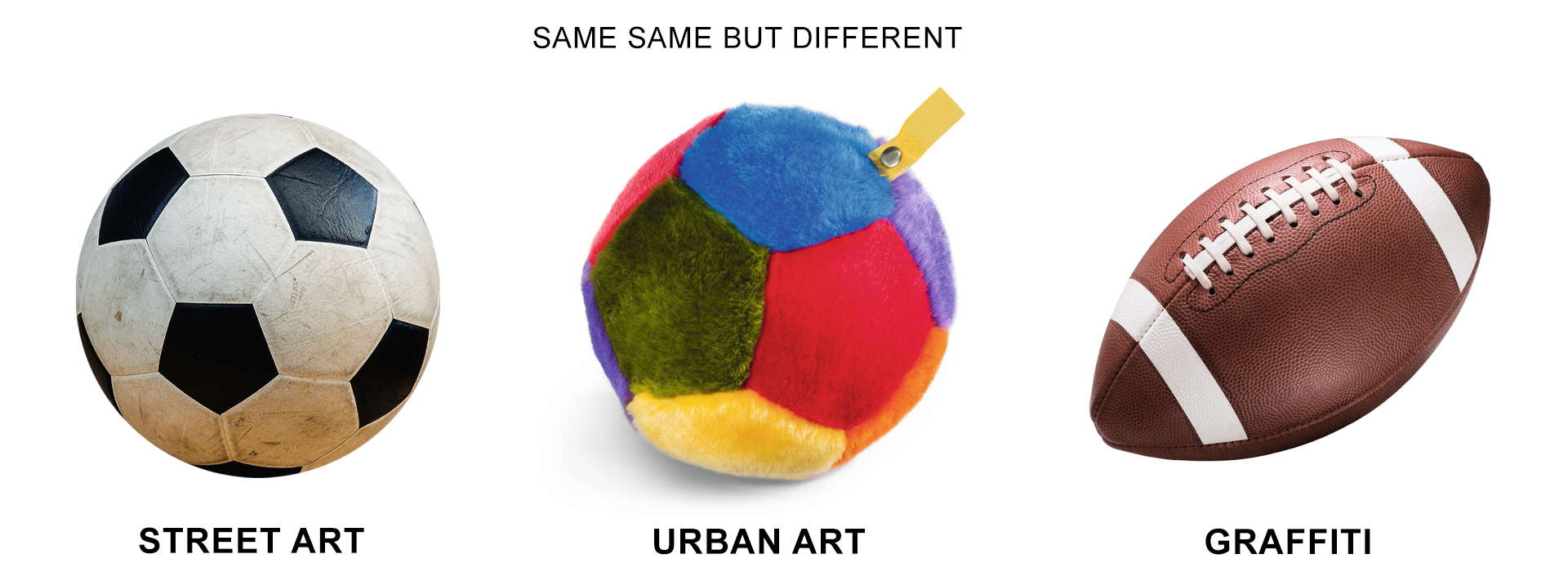

· WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN STREET ART, URBAN ART AND GRAFFITI?

Contrary to the public perception that has established itself since the 2010s thanks to a mixture of misinterpretation and misinformation, street art is not a catch-all term for all art forms created in public spaces – and certainly not for one particular style.

Graffiti, street art and urban art are all very different genres in terms of impact, form and, most of all, intention.

STREET ART - Known since the early 2000s largely through pioneers BANKSY, Mark Jenkins, BLU, Shepard Fairey and INVADER, the street art movement was originally called ‘outsider art’ because its autonomous form and impact could not be classified as conventional graffiti or any other art form. As with graffiti culture before it, street art players made use of public spaces for their art. However, rather than drawing attention to their own names, the aim was to win back public spaces and, in turn, to shine a spotlight on social evils and get people talking about them. Unlike graffiti artists, street art activists don’t draw inspiration from hip-hop culture but rather from the punk rock movement and find their themes on the streets in grassroots movements like anti-war protests or social movements such as Occupy Wall Street, which the artists frequently reference in their works. Another way in which the street art movement differs from conventional graffiti is that it has always made use of the exhibition context and new media (YouTube, Instagram, etc.) as a platform for drawing attention to the social challenges and issues touched upon in their art. There are no more than ten key players in the international street art movement, all of whom plough their own artistic furrow. Even though most of them know and interact with one another privately, it would be a mistake to define them – as some public commentators have done – as a ‘scene’.

URBAN ART – Known exclusively in a commercial context since the end of the 2000s, decorative urban art owes its prominence to the success of the socially critical street art movement but is worlds away from it as regards intention. The term ‘urban art’ was originally coined by gallery owners and art dealers in the late 2000s. The background to this was that both contract sprayers and profit-oriented art dealers had witnessed the popular phenomenon known as street art and were eager to get a piece of the pie. In doing so, they worked primarily with graffiti-sprayers-turned-graphic-designers, inspiring these largely decorative yet subversive canvases with a distinctively Banksy look. As it was clear to both the art dealers and the contract artists at the time that this was not street art in the style of BANKSY, BLU, etc., it was agreed to call it ‘urban art’ instead, given that the studios were normally found in urban settings.

Italian muralist and street art pioneer BLU set up a website called Urbansh.it to counter wheeling and dealing of this nature. This was followed shortly afterwards by BANKSY’s mockumentary ‘Exit Through The Gift Shop’, originally intended as a critical statement on the growing commercialisation that was watering down the socio-critical street art movement with banal urban art.

However, the well-intentioned move backfired for the street art movement and the Pandora’s box has remained wide open ever since. For instance, some self-distributed publications have been peddling ‘street art’ tours along legal graffiti commissions and open spaces and ‘museums’ and art dealers have been hiring contract artists to create new works. These actions only serve to trivialise the original intention of the street art movement, reinforcing their own personal definition of ‘street art’ in the public eye as a byword for garish and often amateurish pictures in public spaces.

GRAFFITI - Graffiti culture, which has now taken root all over the world, originated largely in New York style writing and the hip-hop culture of the 1970s/1980s and ranges from tags and lettering to elaborate concept walls that can also include figurative elements. The artists on the graffiti scene are mainly concerned with spreading their own names in public spaces and communicating with and acknowledging other members of their closed scene. Because of the risk of prosecution, most of them choose to shun the public spotlight and remain anonymous. For the most part, conventional graffiti remains unauthorised and non-commercial to this day.

· WHY IS THE AMUSEUM A MUSEUM AND NOT A GALLERY?

Even though the term ‘museum’ is not legally protected and even companies operating on a purely commercial basis can call themselves a museum, the International Council of Museums – to which both the Louvre in Paris and the AMUSEUM of Contemporary Art belong – stipulates clear guidelines for the definition of a museum:

“A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability.”

A museum works on the basis of professional structures, communicating cultural values on ethical grounds, in the public’s interest, and independent from any commercial objectives or personal preferences. It provides a broad public with varied experiences in terms of education, pleasure, reflection and knowledge sharing.

These community-oriented values differentiate a public museum from a commercial gallery or an exhibition venue that refers to itself as a museum.

· WHY IS AMUSEUM THE FIRST STREET ART MUSEUM?

The AMUSEUM of Contemporary Art is the world’s first and (so far) only institution that develops, plans and carries out exhibitions in direct cooperation with the most influential artists from the international street art movement. AMUSEUM is also the only museum to date that operates according to the guidelines set out by the International Council of Museums.

The authentic foundation of the museum’s work is based on the ongoing collaboration of the art association Positive-Propaganda, under the artistic direction of Sebastian Pohl, together with the pioneers and key players of the street art movement – including Shepard Fairey, BLU, Mark Jenkins, ESCIF, NoNÅME, FAILE and INVADER – which has been going strong for more than a decade. This authentic exchange gives rise to the unique opportunity of following and documenting at first hand the stories and creative pursuits of the largely publicity-shy art activists, most of whom prefer to remain anonymous in their work.

Beyond that, AMUSEUM also has access to one of the most important art collections, including a variety of artworks from the street art movement.

· DOES THE MUSEUM OFFER GUIDED TOURS OF THE CURRENT EXHIBITIONS?

Every second Thursday in the month, AMUSEUM offers art enthusiasts a free guided tour developed in collaboration with the artists. By prior arrangement, it is also possible to request private guided tours for individuals or groups during the regular opening hours (for a fee). Further details can be requested via the contact form.

· IS IT POSSIBLE TO PURCHASE THE EXHIBITED ARTWORKS?

As non-profit institutions, neither AMUSEUM nor the art association Positive-Propaganda, sells the artworks shown in the exhibitions. But with the support of Overrated Art Inc., the museum offers editions donated by the artists.

If the artworks shown in the exhibition are in the artist’s possession, the artist is free to sell their work after the exhibition.

· CAN I HIRE THE AMUSEUM VENUE FOR EVENTS?

Due to the museum’s non-profit orientation and non-commercial exhibition concept, the premises are not available to hire for any kind of external exhibitions or events.

· MAY I TAKE PHOTOS OF THE ARTWORKS IN THE MUSEUM?

Taking photos (without a flash or tripod) and filming the artworks for personal, non-commercial use is generally permitted, provided you credit the artist.

· AS AN ARTIST, CAN I EXHIBIT MY WORK AT AMUSEUM?

The AMUSEUM of Contemporary Art works with a well-versed team on the planning and realisation of long-term exhibitions. Preparations for future exhibitions currently take up to five years and also depend on the individual funding available. As the exhibition line-up has already been planned years in advance, it will not be possible to initiate any external exhibition projects in the near future.

· IS IT POSSIBLE TO FILM INSIDE AMUSEUM?

Film recordings inside the museum and of the exhibitions may be permitted (in the context of film projects and reports related to the exhibition content) after prior arrangement. If you wish to film at our museum, please send us a detailed concept or more precise information about what you are planning in advance.